A number of Georgia Confederate soldiers struggled to survive at various Federal hell-hole prisons well after the war ended in Virginia. The 35th Georgia Infantry Regiment’s private John Frank Edwards was captured at Fort Gregg [The Confederate Alamo] on April 2, 1865. His scary story begins at the Union supply depot at City Point near Petersburg where he boarded a boat full of fellow prisoners – destination unknown.

Pvt. Frank Edwards, Co. D, 35th Georgia Infantry Regiment

Edwards recalled, “we went out on the boats toward hell, if you will excuse the expression. It proved to be a veritable hades.” The disgruntled prisoners were unsure of their destination as the boat weighed anchor and steamed down the James River. Uncertainty weighed heavily on the twenty-two-year-old Edwards. “Those seemed to be the darkest days of my life, hard fighting, thirsty, hungry, half clad, no future, our army almost gone, so many of our brave heroes killed on the battlefield, our homes burned, our cities destroyed and we prisoners of war, out on the waters of the great ocean, and did not know where we would land.” He did not believe the written word could really describe how black that night really was. His only consolation, which he called a privilege, was his ability to pray to God for protection.

On the afternoon of April 5, the boat docked at the wharf for Point Lookout, Maryland. Black soldiers in blue uniforms came on board and ordered the prisoners into a formation. Roll was called and two prisoners were missing. Upon interrogation it was discovered that these two prisoners had jumped overboard in the darkness of night – no doubt to a watery grave. The guards then stripped the men of all their personal items and marched them off the boat toward the looming walls of the prison.

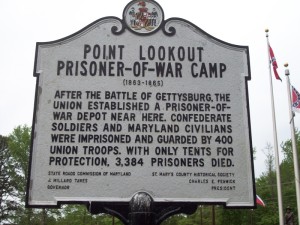

Point Lookout, Maryland Prison Camp

Point Lookout, Maryland, was established on a long sandy point where the Potomac River ran into the Chesapeake Bay. The first prisoners arrived shortly after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. The camp was almost at sea level thus drainage was poor and the area was subjected to high winds and temperature extremes. Point Lookout was the only Federal prison that did not use barracks to house the prisoners, but instead only tents. It was the largest Union prison camp of the war and held not only thousands of Georgia Confederates but soldiers from every state in the Confederacy. During its two-year existence, the tall walls held more than 52,000 military and civilian prisoners. Some 3,000 of these prisoners perished due to the squalid conditions.

A fifteen foot high wooden fence surrounded the prison. Frank Edwards received a close call shortly after his arrival:

“We found about twenty-five thousand prisoners on ten acres of land, which of course, made it very much crowded. I passed on to the lower side. I thought I would step up to the wall and see how far it was to the Chesapeake Bay. I heard several of the men saying, ‘Come back! Come back! You will get killed. Don’t you see that ditch; don’t step across that ditch or you will be killed.’ I was just in the act of stepping over the ditch; only two more steps to carry me over. I looked up and saw a negro guard ready to shoot me when I stepped over. They said nothing to a prisoner. If one stepped over that ditch he was shot without a word. I was in there only ten minutes and came very near getting shot.”

Point Lookout Prison Camp marker

More on the 35th Georgia Infantry Regiment’s Frank Edwards and his Point Lookout experience to continue in next post.

NOTES

Army Life of Frank Edwards – Confederate Veteran – Army of Northern Virginia 1861-1865. (1906). John Frank Edwards p.41-42, 46.

Red Clay to Richmond: Trail of the 35th Georgia Infantry Regiment by John J. Fox, Angle Valley Press, 2004, p. 328.

Speak Your Mind